Seata, short for Simple Extensible Autonomous Transaction Architecture, is an all-in-one distributed transaction solution. It provides AT, TCC, Saga, and XA transaction modes. This article provides a detailed explanation of the Saga mode within Seata, with the project hosted on GitHub.

Author: Yiyuan (Chen Long), Core Developer of Distributed Transactions at Ant Financial.

Pain Points in Financial Distributed Application Development

Distributed systems face a prominent challenge where a business process requires a composition of various services. This challenge becomes even more pronounced in a microservices architecture, as it necessitates consistency guarantees at the business level. In other words, if a step fails, it either needs to roll back to the previous service invocation or continuously retry to ensure the success of all steps. - From "Left Ear Wind - Resilient Design: Compensation Transaction"

In the domain of financial microservices architecture, business processes are often more complex. Processes are lengthy, such as a typical internet microloan business process involving calls to more than ten services. When combined with exception handling processes, the complexity increases further. Developers with experience in financial business development can relate to these challenges.

During the development of financial distributed applications, we encounter several pain points:

-

Difficulty Ensuring Business Consistency

In many of the systems we encounter (e.g., in channel layers, product layers, and integration layers), ensuring eventual business consistency often involves adopting a "compensation" approach. Without a coordinator to support this, the development difficulty is significant. Each step requires handling "rollback" operations in catch blocks, resulting in a code structure resembling an "arrow," with poor readability and maintainability. Alternatively, retrying exceptional operations, if unsuccessful, might lead to asynchronous retries or even manual intervention. These challenges impose a significant burden on developers, reducing development efficiency and increasing the likelihood of errors.

-

Difficulty Managing Business State

With numerous business entities and their corresponding states, developers often update the entity's state in the database after completing a business activity. Lack of a state machine to manage the entire state transition process results in a lack of intuitiveness, increases the likelihood of errors, and causes the business to enter an incorrect state.

-

Difficulty Ensuring Idempotence

Idempotence of services is a fundamental requirement in a distributed environment. Ensuring the idempotence of services often requires developers to design each service individually, using unique keys in databases or distributed caches. There is no unified solution, creating a significant burden on developers and increasing the chances of oversight, leading to financial losses.

-

Challenges in Business Monitoring and Operations; Lack of Unified Error Guardian Capability

Monitoring the execution of business operations is usually done by logging, and monitoring platforms are based on log analysis. While this is generally sufficient, in the case of business errors, these monitors lack immediate access to the business context and require additional database queries. Additionally, the reliance on developers for log printing makes it prone to omissions. For compensatory transactions, there is often a need for "error guardian triggering compensation" and "worker-triggered compensation" operations. The lack of a unified error guardian and processing standard requires developers to implement these individually, resulting in a heavy development burden.

Theoretical Foundation

In certain scenarios where strong consistency is required for data, we may adopt distributed transaction schemes like "Two-Phase Commit" at the business layer. However, in other scenarios, where such strong consistency is not necessary, ensuring eventual consistency is sufficient.

For example, Ant Financial currently employs the TCC (Try, Confirm, Cancel) pattern in its financial core systems. The characteristics of financial core systems include high consistency requirements (business isolation), short processes, and high concurrency.

On the other hand, in many business systems above the financial core (e.g., systems in the channel layer, product layer, and integration layer), the emphasis is on achieving eventual consistency. These systems typically have complex processes, long flows, and may need to call services from other companies (such as financial networks). Developing Try, Confirm, Cancel methods for each service in these scenarios incurs high costs. Additionally, when there are services from other companies in the transaction, it is impractical to require those services to follow the TCC development model. Long processes can negatively impact performance if transaction boundaries are too extensive.

When it comes to transactions, we are familiar with ACID, and we are also acquainted with the CAP theorem, which states that at most two out of three—Consistency (C), Availability (A), and Partition Tolerance (P)—can be achieved simultaneously. To enhance performance, a variant of ACID known as BASE emerged. While ACID emphasizes consistency (C in CAP), BASE emphasizes availability (A in CAP). Achieving strong consistency (ACID) is often challenging, especially when dealing with multiple systems that are not provided by a single company. BASE systems are designed to create more resilient systems. In many situations, particularly when dealing with multiple systems and providers, BASE systems acknowledge the risk of data inconsistency in the short term. This allows new transactions to occur, with potentially problematic transactions addressed later through compensatory means to ensure eventual consistency.

Therefore, in practical development, we make trade-offs. For many business systems above the financial core, compensatory transactions can be adopted. The concept of compensatory transactions has been proposed for about 30 years, with the Saga theory emerging as a solution for long transactions. With the recent rise of microservices, Saga has gradually gained attention in recent years. Currently, the industry generally recognizes Saga as a solution for handling long transactions.

https://github.com/aphyr/dist-sagas/blob/master/sagas.pdf[1] > http://microservices.io/patterns/data/saga.html[2]

Community and Industry Solutions

Apache Camel Saga

Camel is an open-source product that implements Enterprise Integration Patterns (EIP). It is based on an event-driven architecture and offers good performance and throughput. In version 2.21, Camel introduced the Saga EIP.

The Saga EIP provides a way to define a series of related actions through Camel routes. These actions either all succeed or all roll back. Saga can coordinate distributed services or local services using any communication protocol, achieving global eventual consistency. Saga does not require the entire process to be completed in a short time because it does not occupy any database locks. It can support requests that require long processing times, ranging from seconds to days. Camel's Saga EIP is based on MicroProfile's LRA[3] (Long Running Action). It also supports the coordination of distributed services implemented in any language using any communication protocol.

The implementation of Saga does not lock data. Instead, it defines "compensating operations" for each operation. When an error occurs during the normal process execution, the "compensating operations" for the operations that have already been executed are triggered to roll back the process. "Compensating operations" can be defined on Camel routes using Java or XML DSL (Definition Specific Language).

Here is an example of Java DSL:

// Java DSL example goes here

// action

from("direct:reserveCredit")

.bean(idService, "generateCustomId") // generate a custom Id and set it in the body

.to("direct:creditReservation")

// delegate action

from("direct:creditReservation")

.saga()

.propagation(SagaPropagation.SUPPORTS)

.option("CreditId", body()) // mark the current body as needed in the compensating action

.compensation("direct:creditRefund")

.bean(creditService, "reserveCredit")

.log("Credit ${header.amount} reserved. Custom Id used is ${body}");

// called only if the saga is cancelled

from("direct:creditRefund")

.transform(header("CreditId")) // retrieve the CreditId option from headers

.bean(creditService, "refundCredit")

.log("Credit for Custom Id ${body} refunded");

XML DSL sample:

<route>

<from uri="direct:start"/>

<saga>

<compensation uri="direct:compensation" />

<completion uri="direct:completion" />

<option optionName="myOptionKey">

<constant>myOptionValue</constant>

</option>

<option optionName="myOptionKey2">

<constant>myOptionValue2</constant>

</option>

</saga>

<to uri="direct:action1" />

<to uri="direct:action2" />

</route>

Eventuate Tram Saga

Eventuate Tram Saga[4] The framework is a Saga framework for Java microservices using JDBC/JPA. Similar to Camel Saga, it also adopts Java DSL to define compensating operations:

public class CreateOrderSaga implements SimpleSaga<CreateOrderSagaData> {

private SagaDefinition<CreateOrderSagaData> sagaDefinition =

step()

.withCompensation(this::reject)

.step()

.invokeParticipant(this::reserveCredit)

.step()

.invokeParticipant(this::approve)

.build();

@Override

public SagaDefinition<CreateOrderSagaData> getSagaDefinition() {

return this.sagaDefinition;

}

private CommandWithDestination reserveCredit(CreateOrderSagaData data) {

long orderId = data.getOrderId();

Long customerId = data.getOrderDetails().getCustomerId();

Money orderTotal = data.getOrderDetails().getOrderTotal();

return send(new ReserveCreditCommand(customerId, orderId, orderTotal))

.to("customerService")

.build();

...

Apache ServiceComb Saga

ServiceComb Saga[5] is also a solution for achieving data eventual consistency in microservices applications. In contrast to TCC, Saga directly commits transactions in the try phase, and the subsequent rollback phase is completed through compensating operations in reverse. What sets it apart is the use of Java annotations and interceptors to define "compensating" services.

Architecture:

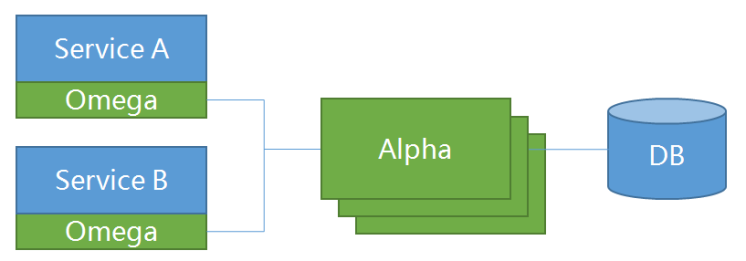

Saga consists of alpha and omega, where:

- Alpha acts as the coordinator, primarily responsible for managing and coordinating transactions;

- Omega is an embedded agent in microservices, responsible for intercepting network requests and reporting transaction events to alpha;

The diagram below illustrates the relationship between alpha, omega, and microservices:

sample:

public class ServiceA extends AbsService implements IServiceA {

private static final Logger LOG = LoggerFactory.getLogger(MethodHandles.lookup().lookupClass());

@Autowired

private IServiceB serviceB;

@Autowired

private IServiceC serviceC;

@Override

public String getServiceName() {

return "servicea";

}

@Override

public String getTableName() {

return "testa";

}

@Override

@SagaStart

@Compensable(compensationMethod = "cancelRun")

@Transactional(rollbackFor = Exception.class)

public Object run(InvokeContext invokeContext) throws Exception {

LOG.info("A.run called");

doRunBusi();

if (invokeContext.isInvokeB(getServiceName())) {

serviceB.run(invokeContext);

}

if (invokeContext.isInvokeC(getServiceName())) {

serviceC.run(invokeContext);

}

if (invokeContext.isException(getServiceName())) {

LOG.info("A.run exception");

throw new Exception("A.run exception");

}

return null;

}

public void cancelRun(InvokeContext invokeContext) {

LOG.info("A.cancel called");

doCancelBusi();

}

Ant Financial's Practice

Ant Financial extensively uses the TCC mode for distributed transactions, mainly in scenarios where high consistency and performance are required, such as in financial core systems. In upper-level business systems with complex and lengthy processes, developing TCC can be costly. In such cases, most businesses opt for the Saga mode to achieve eventual business consistency. Due to historical reasons, different business units have their own set of "compensating" transaction solutions, basically falling into two categories:

-

When a service needs to "retry" or "compensate" in case of failure, a record is inserted into the database with the status before executing the service. When an exception occurs, a scheduled task queries the database record and performs "retry" or "compensation." If the business process is successful, the record is deleted.

-

Designing a state machine engine and a simple DSL to orchestrate business processes and record business states. The state machine engine can define "compensating services." In case of an exception, the state machine engine invokes "compensating services" in reverse. There is also an "error guardian" platform that monitors failed or uncompensated business transactions and continuously performs "compensation" or "retry."

Solution Comparison

Generally, there are two common solutions in the community and industry: one is based on a state machine or a process engine that orchestrates processes and defines compensation through DSL; the other is based on Java annotations and interceptors to implement compensation. What are the advantages and disadvantages of these two approaches?

| Approach | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| State Machine + DSL | - Business processes can be defined using visual tools, standardized, readable, and can achieve service orchestration functionality - Improves communication efficiency between business analysts and developers - Business state management: Processes are essentially state machines, reflecting the flow of business states - Enhances flexibility in exception handling: Can implement "forward retry" or "backward compensation" after recovery from a crash - Naturally supports asynchronous processing engines such as Actor model or SEDA architecture, improving overall throughput | - Business processes are composed of JAVA programs and DSL configurations, making development relatively cumbersome - High intrusiveness into existing business if it is a transformation - High implementation cost of the engine |

| Interceptor + Java Annotation | - Programs and annotations are integrated, simple development, low learning curve - Easy integration into existing businesses - Low framework implementation cost | - The framework cannot provide asynchronous processing modes such as the Actor model or SEDA architecture to improve system throughput - The framework cannot provide business state management - Difficult to achieve "forward retry" after crash recovery due to the inability to restore thread context |

Seata Saga Approach

The introduction of Seata Saga can be found in Seata Saga Official Documentation[6].

Seata Saga adopts the state machine + DSL approach for the following reasons:

- The state machine + DSL approach is more widely used in practical production scenarios.

- Can use asynchronous processing engines such as the Actor model or SEDA architecture to improve overall throughput.

- Typically, business systems above the core system have "service orchestration" requirements, and service orchestration has transactional eventual consistency requirements. These two are challenging to separate. The state machine + DSL approach can simultaneously meet these two requirements.

- Because Saga mode theoretically does not guarantee isolation, in extreme cases, it may not complete the rollback operation due to dirty writing. For example, in a distributed transaction, if you recharge user A first and then deduct the balance from user B, if A user consumes the balance before the transaction is committed, and the transaction is rolled back, there is no way to compensate. Some business scenarios may allow the business to eventually succeed, and in cases where rollback is impossible, it can continue to retry the subsequent process. The state machine + DSL approach can achieve the ability to "forward" recover context and continue execution, making the business eventually successful and achieving eventual consistency.

In cases where isolation is not guaranteed: When designing business processes, follow the principle of "prefer long 款, not short 款." Long 款 means fewer funds for customers and more funds for institutions. Institutions can refund customers based on their credibility. Conversely, short 款 means less funding for institutions, and the funds may not be recovered. Therefore, in business process design, deduction should be done first.

State Definition Language (Seata State Language)

-

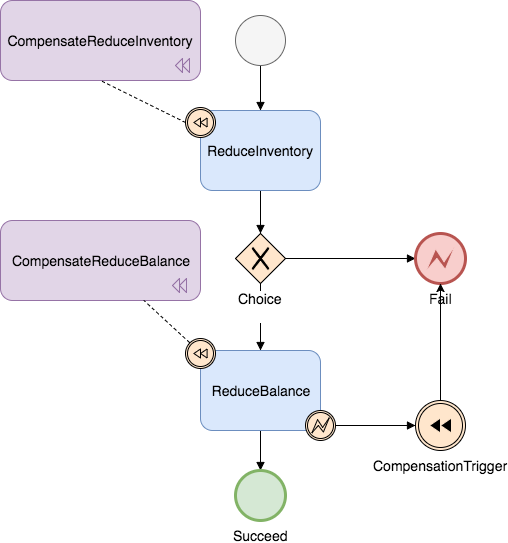

Define the service call process through a state diagram and generate a JSON state language definition file.

-

In the state diagram, a node can be a service call, and the node can configure its compensating node.

-

The JSON state diagram is driven by the state machine engine. When an exception occurs, the state engine executes the compensating node corresponding to the successfully executed node to roll back the transaction.

Note: Whether to compensate when an exception occurs can also be user-defined.

-

It can meet service orchestration requirements, supporting one-way selection, concurrency, asynchronous, sub-state machine, parameter conversion, parameter mapping, service execution status judgment, exception capture, and other functions.

Assuming a business process calls two services, deducting inventory (InventoryService) and deducting balance (BalanceService), to ensure that in a distributed scenario, either both succeed or both roll back. Both participant services have a reduce method for inventory deduction or balance deduction, and a compensateReduce method for compensating deduction operations. Let's take a look at the interface definition of InventoryService:

public interface InventoryService {

/**

* reduce

* @param businessKey

* @param amount

* @param params

* @return

*/

boolean reduce(String businessKey, BigDecimal amount, Map<String, Object> params);

/**

* compensateReduce

* @param businessKey

* @param params

* @return

*/

boolean compensateReduce(String businessKey, Map<String, Object> params);

}

This is the state diagram corresponding to the business process:

Corresponding JSON

{

"Name": "reduceInventoryAndBalance",

"Comment": "reduce inventory then reduce balance in a transaction",

"StartState": "ReduceInventory",

"Version": "0.0.1",

"States": {

"ReduceInventory": {

"Type": "ServiceTask",

"ServiceName": "inventoryAction",

"ServiceMethod": "reduce",

"CompensateState": "CompensateReduceInventory",

"Next": "ChoiceState",

"Input": ["$.[businessKey]", "$.[count]"],

"Output": {

"reduceInventoryResult": "$.#root"

},

"Status": {

"#root == true": "SU",

"#root == false": "FA",

"$Exception{java.lang.Throwable}": "UN"

}

},

"ChoiceState": {

"Type": "Choice",

"Choices": [

{

"Expression": "[reduceInventoryResult] == true",

"Next": "ReduceBalance"

}

],

"Default": "Fail"

},

"ReduceBalance": {

"Type": "ServiceTask",

"ServiceName": "balanceAction",

"ServiceMethod": "reduce",

"CompensateState": "CompensateReduceBalance",

"Input": [

"$.[businessKey]",

"$.[amount]",

{

"throwException": "$.[mockReduceBalanceFail]"

}

],

"Output": {

"compensateReduceBalanceResult": "$.#root"

},

"Status": {

"#root == true": "SU",

"#root == false": "FA",

"$Exception{java.lang.Throwable}": "UN"

},

"Catch": [

{

"Exceptions": ["java.lang.Throwable"],

"Next": "CompensationTrigger"

}

],

"Next": "Succeed"

},

"CompensateReduceInventory": {

"Type": "ServiceTask",

"ServiceName": "inventoryAction",

"ServiceMethod": "compensateReduce",

"Input": ["$.[businessKey]"]

},

"CompensateReduceBalance": {

"Type": "ServiceTask",

"ServiceName": "balanceAction",

"ServiceMethod": "compensateReduce",

"Input": ["$.[businessKey]"]

},

"CompensationTrigger": {

"Type": "CompensationTrigger",

"Next": "Fail"

},

"Succeed": {

"Type": "Succeed"

},

"Fail": {

"Type": "Fail",

"ErrorCode": "PURCHASE_FAILED",

"Message": "purchase failed"

}

}

}

This is the state language to some extent referring to AWS Step Functions[7].

Introduction to "State Machine" Attributes:

- Name: Represents the name of the state machine, must be unique;

- Comment: Description of the state machine;

- Version: Version of the state machine definition;

- StartState: The first "state" to run when starting;

- States: List of states, a map structure, where the key is the name of the "state," which must be unique within the state machine;

Introduction to "State" Attributes:

- Type: The type of the "state," such as:

- ServiceTask: Executes the service task;

- Choice: Single conditional choice route;

- CompensationTrigger: Triggers the compensation process;

- Succeed: Normal end of the state machine;

- Fail: Exceptional end of the state machine;

- SubStateMachine: Calls a sub-state machine;

- ServiceName: Service name, usually the beanId of the service;

- ServiceMethod: Service method name;

- CompensateState: Compensatory "state" for this state;

- Input: List of input parameters for the service call, an array corresponding to the parameter list of the service method, $. represents using an expression to retrieve parameters from the state machine context. The expression uses SpringEL[8], and if it is a constant, write the value directly;

- Output: Assigns the parameters returned by the service to the state machine context, a map structure, where the key is the key when placing it in the state machine context (the state machine context is also a map), and the value uses $. as a SpringEL expression, indicating the value is taken from the return parameters of the service, #root represents the entire return parameters of the service;

- Status: Mapping of the service execution status, the framework defines three statuses, SU success, FA failure, UN unknown. We need to map the execution status of the service into these three statuses, helping the framework judge the overall consistency of the transaction. It is a map structure, where the key is a condition expression, usually based on the return value of the service or the exception thrown for judgment. The default is a SpringEL expression to judge the return parameters of the service. Those starting with $Exception{ indicate judging the exception type, and the value is mapped to this value when this condition expression is true;

- Catch: Route after catching an exception;

- Next: The next "state" to execute after the service is completed;

- Choices: List of optional branches in the Choice type "state," where Expression is a SpringEL expression, and Next is the next "state" to execute when the expression is true;

- ErrorCode: Error code for the Fail type "state";

- Message: Error message for the Fail type "state";

For more detailed explanations of the state language, please refer to Seata Saga Official Documentation[6http://seata.io/zh-cn/docs/user/saga.html].

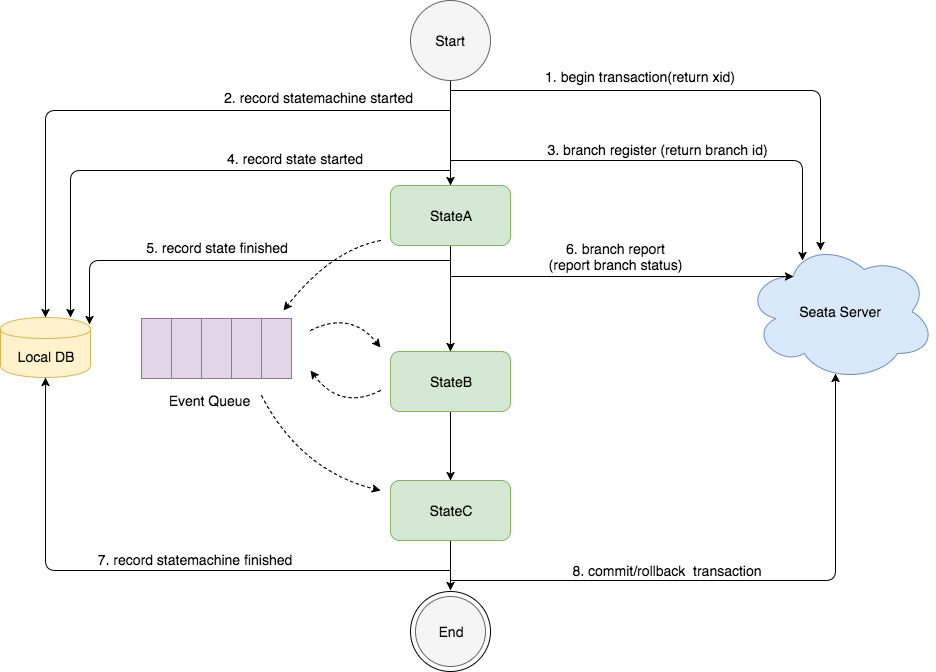

State Machine Engine Principle:

- The state diagram in the image first executes stateA, then executes stateB, and then executes stateC;

- The execution of "states" is based on an event-driven model. After stateA is executed, a routing message is generated and placed in the EventQueue. The event consumer takes the message from the EventQueue and executes stateB;

- When the entire state machine is started, Seata Server is called to start a distributed transaction, and the xid is generated. Then, the start event of the "state machine instance" is recorded in the local database;

- When a "state" is executed, Seata Server is called to register a branch transaction, and the branchId is generated. Then, the start event of the "state instance" is recorded in the local database;

- After a "state" is executed, the end event of the "state instance" is recorded in the local database, and Seata Server is called to report the status of the branch transaction;

- When the entire state machine is executed, the completion event of the "state machine instance" is recorded in the local database, and Seata Server is called to commit or roll back the distributed transaction;

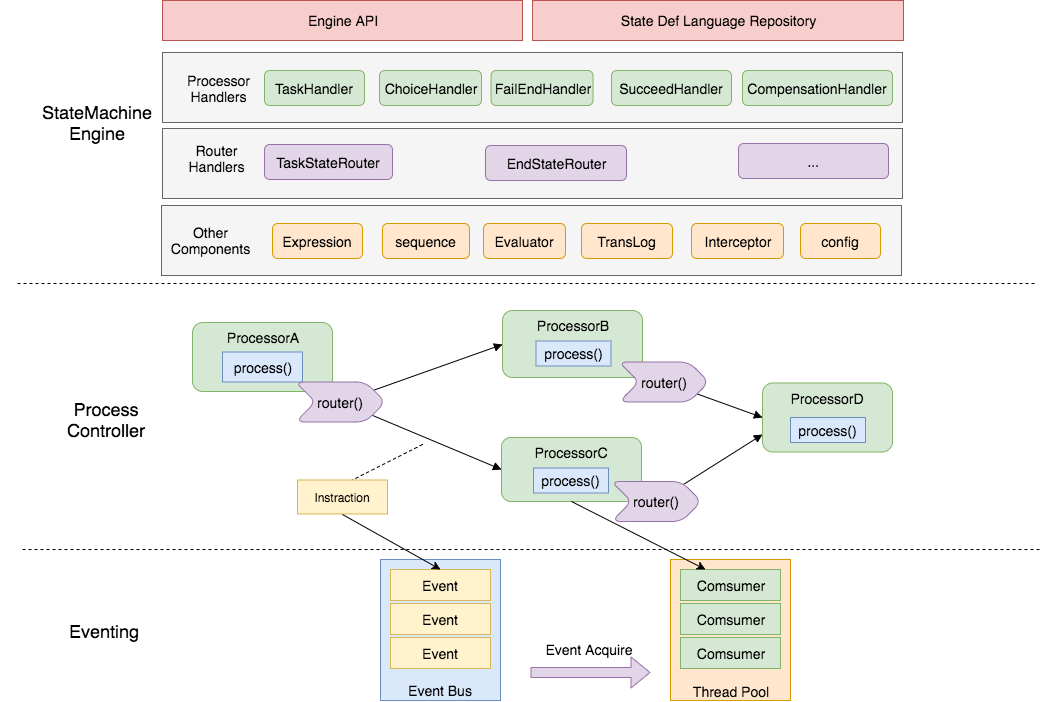

Design of State Machine Engine:

The design of the state machine engine is mainly divided into three layers, with the upper layer depending on the lower layer. From bottom to top, they are:

-

Eventing Layer:

- Implements an event-driven architecture that can push events and be consumed by a consumer. This layer does not care about what the event is or what the consumer executes; it is implemented by the upper layer.

-

ProcessController Layer:

- Driven by the above Eventing to execute a "empty" process. The behavior and routing of "states" are not implemented. It is implemented by the upper layer.

Based on the above two layers, theoretically, any "process" engine can be customly extended. The design of these two layers is based on the internal design of the financial network platform.

- Driven by the above Eventing to execute a "empty" process. The behavior and routing of "states" are not implemented. It is implemented by the upper layer.

-

StateMachineEngine Layer:

- Implements the behavior and routing logic of each type of state in the state machine engine;

- Provides API and state machine language repository;

Practical Experience in Service Design under Saga Mode

Below are some practical experiences summarized in the design of microservices under Saga mode. Of course, these are recommended practices, not necessarily to be followed 100%. There are "workaround" solutions even if not followed.

Good news: Seata Saga mode has no specific requirements for the interface parameters of microservices, making Saga mode suitable for integrating legacy systems or services from external institutions.

Allow Empty Compensation

- Empty Compensation: The original service was not executed, but the compensation service was executed;

- Reasons:

- Timeout (packet loss) of the original service;

- Saga transaction triggers a rollback;

- The request of the original service is not received, but the compensation request is received first;

Therefore, when designing services, it is necessary to allow empty compensation, that is, if the business primary key to be compensated is not found, return compensation success and record the original business primary key.

Hang Prevention Control

- Hang: Compensation service is executed before the original service;

- Reasons:

- Timeout (congestion) of the original service;

- Saga transaction rollback triggers a rollback;

- Congested original service arrives;

Therefore, check whether the current business primary key already exists in the business primary keys recorded by empty compensation. If it exists, reject the execution of the service.

Idempotent Control

- Both the original service and the compensation service need to ensure idempotence. Due to possible network timeouts, a retry strategy can be set. When a retry occurs, idempotent control should be used to avoid duplicate updates to business data.

Summary

Many times, we don't need to emphasize strong consistency. We design more resilient systems based on the BASE and Saga theories to achieve better performance and fault tolerance in distributed architecture. There is no silver bullet in distributed architecture, only solutions suitable for specific scenarios. In fact, Seata Saga is a product with the capabilities of "service orchestration" and "Saga distributed transactions." Summarizing, its applicable scenarios are:

- Suitable for handling "long transactions" in a microservices architecture;

- Suitable for "service orchestration" requirements in a microservices architecture;

- Suitable for business systems with a large number of composite services above the financial core system (such as systems in the channel layer, product layer, integration layer);

- Suitable for scenarios where integration with services provided by legacy systems or external institutions is required (these services are immutable and cannot be required to be modified).

Related Links Mentioned in the Article

[1]https://github.com/aphyr/dist-sagas/blob/master/sagas.pdf

[2]http://microservices.io/patterns/data/saga.html

[3]Microprofile 的 LRA:https://github.com/eclipse/microprofile-sandbox/tree/master/proposals/0009-LRA

[4]Eventuate Tram Saga:https://github.com/eventuate-tram/eventuate-tram-sagas

[5]ServiceComb Saga:https://github.com/apache/servicecomb-pack

[6]Seata Saga 官网文档:http://seata.io/zh-cn/docs/user/saga.html

[7]AWS Step Functions:https://docs.aws.amazon.com/zh_cn/step-functions/latest/dg/tutorial-creating-lambda-state-machine.html

[8]SpringEL:https://docs.spring.io/spring/docs/4.3.10.RELEASE/spring-framework-reference/html/expressions.html